I'm going to side track from the First World War a bit to talk about my great-grandmother, Jack's wife, Alma Kerr.

Alma Kerr was born to Francis "Frank" Kerr and Icey Leake on December 22nd, 1895, in Simcoe, Ontario. The Kerr family originally hailed from Ireland, with Alma's grandfather, Sam Kerr, immigrating to Canada sometime in the 1840's. The family was quite prosperous (they owned a brick yard) and well known in Simcoe. Sam Kerr had married into an old Dutch family (the Vandervoorts) Sometime after 1901, the Kerr family had moved from Simcoe to the East End of Toronto (at 195 Greenwood Ave) where Frank Kerr worked in a tannery.

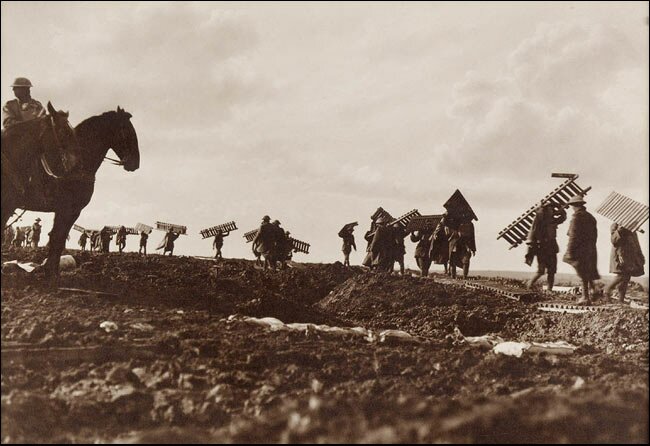

the brickyard

I am not clear on how Alma and Jack met but they were married on June 15th 1915 in Toronto. From what my Aunt (my source for all this information) had told me is that the Kerr family (especially Frank)did not like Jack at all. I have never heard the reason why this was. It was from these conversations with my Aunt, that she told me that Jack lied his whole life about being a Methodist (the Kerr's were Methodists.) Jack's family had been Catholic and Jack had been raised Catholic. The Kerr family though, didn't like Catholics. Alma certainly knew, as she was the one who told me Aunt many years later, but it all most certain that Frank Kerr and the rest did not know. If they did, Alma would never have been allowed to marry Jack.

Jack and Alma moved into 123 Greenwood St (which was bought by Frank Kerr)just after the wedding. Around this time Frank and Isey moved in with them. In February 1916, Jack enlisted in the CEF and shipped off a few months later to England. This time in my great-grandmother's life is a mystery, all I know is (from reviewing Jack's service record) that Alma received a separation allowance every month from Jack's pay.

In 1919, Jack returned to Canada and began work at the same tannery as Frank Kerr. This did not last long as Jack could not stand the smell of the place and soon found work with Ontario Hydro. In 1920, Jack and Alma had their first child, my grandad, Frank Dowe. He was followed in quick succession by Edward, (who died in WWII)Milton and Patricia.

Jack and Alma lived in Toronto till the late 60's, when they finally moved to Ottawa at he request of my grandad. Jack had been suffering from diabetes and was becoming difficult to care for at home. On December 22nd, 1969 (Alma's birthday) Jack died. For the next twenty years, Alma lived close to her remaining family. She died in 1990 at the age of 95.